Crash Read online

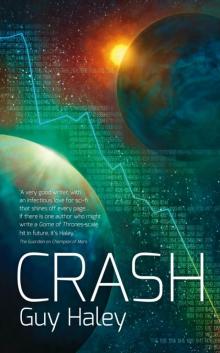

Praise for Guy Haley

‘A very good writer, with an infectious love for sci-fi that shines off every page...

If there is one author who might write a Game of Thrones-scale hit in future, it’s Haley.’

Damien G. Walter, The Guardian on Champion of Mars

‘It’s a thriller, an unnatural mystery and a strange sort of love story.

Highly entertaining and original, and well worth a look.’

Starburst Magazine on Champion of Mars

‘A big think on the issues raised by the existence of Articial Intelligence in society.’

I Will Read Books on Reality 36

‘Guy Haley is a hidden gem of British SF.’

Paul Cornell

Also by Guy Haley

Champion of Mars

Reality 36

Omega Point

First published 2013 by Solaris

an imprint of Rebellion Publishing Ltd,

Riverside House, Osney Mead,

Oxford, OX2 0ES, UK

www.solarisbooks.com

ISBN: (epub) 978-1-84997-580-3

ISBN: (mobi) 978-1-84997-581-0

Copyright © Guy Haley 2013

Cover Art by Pye Parr

The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of he copyright owners.

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are fictional, and any resemblance to real people or incidents is purely coincidental.

It is in the interest of mankind, not simply of those of us fortunate to be burdened with the task of wealth creation and prosperity maintenance, to step outside the bounds of our solar cage, and commence the great adventure that has awaited our kind since the first time a man raised his eyes to the stars.

The Earth is not room enough. Mankind requires space to grow, the Market requires space to grow. Only in the great, limitless spaces of the cosmos will our species find what it requires to spread the noble cause of human persistence into the deep time of the future. We are in the process of conquering the Solar System, but only beyond the great gulfs of interstellar space are gentler worlds found, places where mankind may not merely survive, not just harvest materials to be sent to the motherworld, but truly prosper and spread in glorious diaspora.

We live in a time where the majority of the wealth is held by a minority of the people. I admit that this number includes myself. I have striven all my life to use my wealth to improve the quality of life of my fellow citizens, but some time ago I came to the realisation that we must head out and onwards, as the first true men did when they left Africa and walked in triumph across the globe. As the pioneering men and women who crossed to Australia and America in the forgotten past did, as the great explorers in the age of mercantilism sailed the oceans in search of new markets, so will we sail the stars and found new outposts of mankind. With space to multiply and create new worlds rich with opportunity for all, the people of Earth will be granted the chance to exercise their capabilities to the full. This is an age of new pioneers, of new opportunities. Our success here on Earth has been our downfall, we are too many for all to be free, we have used too much for everyone to be wealthy. The inequality we see every day is the product not of human selfishness, but of the natural constraints of our environment. Through the Gateway Project, we will fling open the doors of the prison, and humankind will stand astride the stars of the galaxy as a new-minted colossus. From this day forth, wealth will no longer be restricted to the few; all humanity might share in the universe’s bounty.

– Part of the speech delivered by John Karlton, CEO of Lodestone Inc., at the official launch of the Gateway Project. Tokyo, Japan, June 25th, 2153

In the wake of the financial collapses of the early 21st century, living standards dropped across what was then termed the ‘developed world,’ in essence those states of Europe and their former colonies where the original inhabitants had been extirpated and a European society established... As we have seen, the consequences of the Third Industrial Revolution were far-reaching, overturning much of contemporary economic thought. In a grand twist of irony those who could still find employment reverted to a semi-artisanal state not dissimilar to that experienced by their ancestors, before the First Industrial Revolution concentrated the new worker class in the new towns and cities of that time.

Despite the optimistic predictions of various commentators, chief among them Eisenstein, Korolev and Kang, there could be no return to a pre-industrial state. Over-population became the issue that it still is today, and although we evade the doom of Malthus, another, more insidious lack than the shortage of food became pressing – employment. Successive technological advances throughout the 20th and 21st centuries led to a vast over-provision of able bodied workers... Not for them the leisured lifestyle predicted by the futurists of the 1950s, but one of poverty and marginalisation. In an economy driven by the accumulation of wealth, the absence of the means to accumulate money effectively excluded an increasingly large proportion of the world population from both the benefits of advanced science, and from an engagement with any form of power structure.

One class did, however, prosper in these times. That exclusive echelon of the social order known now as ‘The Pointers’ was drawn from the more financially robust members of Western Europe’s ancient aristocracies, scions of industrial families enriched in the first two industrial revolutions, clans of oligarchs enriched by the collapse of communism, and those catapulted into the realms of megawealth by the financialisation of business in the 1990s and early 2000s and the growth of celebrity-worship. This concentration of wealth in the hands of the few is sadly not unique to our time or situation. What is different about the Pointers is their longevity; much like the aristocracies of Medieval Europe and Asia, they have lasted. During the centuries of industrialisation, society became fluid; to lesser or greater degrees dependent on the precise era, with the great wealth generated by any one family as often as not lost within the space of a century... and now in this consequent period, this social mobility has ceased...

In the Medieval Period, agriculturally productive land was the source of all wealth. Control of it and those who worked it became ever more entrenched within the class of the nobility. Revolution and rebellion did little to unseat this; it was only when new means of creating large fortunes came into being that this ancien régime was truly challenged, and eventually toppled.

As is the way with all human activity, the accumulation of virtually all wealth by one small class of people has proved cyclical. Over the course of the last 250 years, the Pointers have arisen from the industrialists, merchants and financiers who toppled the prior land-based hierarchy...

...in the case of the Pointers, prominence is due to their domination of a finite resource; not actual, physical resources as in prior aristocracies, although many of these families attained their wealth through the monopolisation of the production of raw materials. The resource the Pointers so jealously guard is wealth itself. So abstract a source of power it is at once ridiculous and unassailable. Ridiculous, because their superiority is effectively built on the compliance of those they oppress – money, unlike land, is a fiction. Unassailable, as its illusory nature makes it extremely easy to totally control. The Pointers have become adept at protecting this wealth, for we live in a time where only wealth generates wealth. Virtually all avenues to the creation of wealth have been shut off or are entirely in the hands of the Pointers. Only the Pointers have the money

to invest in the creation of more money, and as the protection of their finances has been removed from their direct control and placed in the phantom hands of virtually infallible, multi-generational algorithms, it seems their grip on power is even more tenacious than that of the medieval robber barons. Furthermore, the assets the Pointers command are so vast, that their fortunes make the worst excesses of ancient emperors seem restrained by comparison.

– Excerpt from one of Professor Todeo Hiyazaki’s series of banned lectures on the Pointer families

PROLOGUE

AT FIRST, DARIUSZ Szczeciński was dead, then he was not.

Machines hurried him to life more quickly than they should. Preservative fluids were sucked from his circulatory system with haste, warmed blood pumped into their place. Mechanisms whose own time was shortly to come ran cursory checks, the provenance of emergency. High percentiles were lowered, risks were taken that would not ordinarily have been taken. For long seconds, the essence of Dariusz hung upon the fences that separate the living from the dead.

Bursts of electricity massaged his heart to activity. Neurons long dormant sparkled, chains of lightning arced through ganglia. Briefly raging, the storm of activity housed by his skull flickered out once more.

The machines noted. The machines adjusted. The machines applied the correct voltage just so, recalibrated their potions of amino acids and adrenaline. They ministered to their charge diligently and with grace as death rode down upon them.

Dariusz stirred in his coffin. The miracle of consciousness prepared itself to manifest. The machines felt no satisfaction. Their power supply dwindled. The machines felt no fear.

The not-quite-mind of the deck segment allowed the revivification process to run its course, and turned from Dariusz to save as many others as it could before its own feeble unlife was extinguished.

Pseudo-amniotic liquid drained. Dariusz awoke slowly. He felt nothing, at first; nothing but the cold and a hazy contentment, denying him awareness of the peril of his situation. That was a mercy.

A pleasant chime announced his reanimation.

His wellbeing, chemically donated by the sarcophagus, was fleeting. He blinked eyes sticky with amniotics, and coughed violently, bringing up a sheeting flood of the same. He was on his side, rather than half-reclined. Gravity greater than Earth normal pulled at him uncomfortably. His face was pressed into the front of the sarcophagus. Fear penetrated his post-hibernation fug. He could not get out! The lid – the lid was stuck. It made feeble clicking noises, reached a point at which it jammed, then arthritically shut again, jarring his face. Repeat.

Dariusz braced himself against the back of the sarcophagus and kicked against the lid. He was weak; his feet, numb with cold and slick with the fluids of the deathsleep, skidded on the plastic. His body shook. He wriggled feebly, until he gained himself a better situation. He arched his back against the moulded hibernation couch, doubled over into a foetal position, feet braced on the lid. He waited for the lid to cycle back to the start of its failed opening, and pushed with his legs. He grunted with effort as the door attempted to close again. The lid was ignorant of his desire to escape, and its mechanisms pushed cruelly against him. Panic lent him strength, he made animal noises as he fought his weakened muscles, something tore in his back. His constricted neck made it difficult to breathe. His existence contracted to a point of pressure, flesh against machine. And then, release. The lid ceased pushing and began to open once more. He followed its motion with a hard shove. The lid opened a fraction further, he heard a scraping as the mechanism caught, there was wild hissing as pneumatics burst. Resistance abruptly ceased, and the door flew open.

Dariusz tumbled with it. His slippery body skidded from the pod, falling sideways. The topography of the deck was all to hell: the floor was a canted wall, and the corridor had become a gaping pit.

Dariusz bounced from the smooth surfaces of other sarcophagi, banged painfully into an open lid. The air in his lungs, so recently replenished, was knocked from him. He tore his arm on jagged carbon, skidded as the curve levelled, and plunged into a thick pond of spilled amniotics gathered at the bottom. Stunned, he sank into the morass, and it had him. The hibernation deck had become a pitcher trap.

The amniotics made a milky nowhere, featureless as the womb; not dark, but a dirty whiteness in all directions. Its density lent him buoyancy; up from down became an impossible guess. He thrashed. His newly woken lungs burned, the need to open his mouth and suck in the fluid he knew would kill him passed from urge to necessity.

His feet found smooth, hard plastic. He pushed off hard, only to slip. The fluid was slicker than oil. He fought his body’s demands to breathe as hard as he fought the amniotic’s grip.

Without warning, he was free. His head broke the surface. At first he could not tell, so viscously the fluid clung, until it ran from him in reluctant streams and he took a roaring breath of the ship’s stale air, pulling the sharp reek of the pseudo-amniotics, the tang of burnt plastics, charred metal, and putrescence into his lungs.

Thus was Dariusz reborn on a new world.

Fluid sprayed from him as he flailed to and fro, still wild from his struggle. He locked eyes with a startled woman. Naked like he, her hair as closely cropped as his, as weak as he was, gaunt as a ghost. Her breasts were flat against her chest. In her thin arms she cradled the head and shoulders of an unconscious man.

A muffled banging came from overhead. Dariusz looked up. Through the viewport of a sarcophagus, he caught the outline of a face. It vanished into greyness and fluid filled the pod.

“We’ve landed end on, and at an angle,” said the woman. Her voice was a surprise; Dariusz had forgotten speech. “The fluid is not draining away. They’re going to drown.” She said this matter-of-factly, eyes on the pod. She was observing, as one might observe the death of an animal in the wild – dispassionately, scientifically almost. Her lips were compressed into thin lines. She shook hard from the chill of the amniotics pool, but made no attempt to escape from it. Her skin was grey.

Dariusz looked around for something, anything, to push the window in and release the trapped fluid. The thumping on the lid grew more frantic. Dariusz bent down and searched the pool’s floor, but his fingers encountered only smooth edges. There was one final thump, and then nothing.

They watched as the pod completed the revivification cycle and opened. A young man tumbled out, limp and lifeless. He landed in the pool face down. It took four attempts for Dariusz to hook his hands under the body and roll it over. He pressed his fingers to the man’s neck. There was no pulse.

The woman looked on, face blank, as Dariusz pulled the man to the edge of the pool. He rested him as well as he could on the curving wall of sarcophagi. CPR proved nigh on impossible. Dariusz was weak. The liquid had lost none of its chill, and he shivered in great, quaking spasms. His hands slipped as he worked the man’s arms to pump his lungs free of the amniotics. When he had done this, he struggled to roll him over, nearly losing him to the pool twice. He pounded with feeble linked fists on his chest, pausing to put his own freezing lips onto the man’s. They were both as cold as corpses.

“I don’t know why you bother,” said the woman. “We’re all dead anyway.”

Dariusz glared back at her, although he feared the truth of what she said. He persisted in his efforts for fifteen, twenty minutes, but he was not so skilled as the machines at bringing back the dead.

Exhausted, he stopped, and the man’s corpse slid into the pool. He did not, could not, stop it. It sank face down, until only ridge of his shoulders and the nub of his skull showed. Dariusz stared, his eyes drawn to a marbling of red in the white liquid. He had forgotten he had cut himself. He felt no pain. He was too tired to check how badly he was hurt.

He turned to the woman. She returned his stare unblinkingly.

“You are wrong,” said Dariusz. His voice croaked. It was not this bad last time he woke.

Last time? There had been a last time. Fragmentary memories

flitted through him, elusive and unwilling to give up their secrets. Dread clutched at him, bringing with it a feeling of profound responsibility.

He remembered something else, a vivid flash of a briefing. He was no longer in the freezing pool, but elsewhere, a hundred years away. The man in the suit, with eyes in bruised sockets, said: hibernation sickness worsens, the longer one is under. The flash went, bright and painful light in his eyes. He tried his inChip; there was no response. Other memories burst into being, brief as fireworks. His sense of self cracked. He was close to dissolution. Weakness, organ damage, brain damage, psychosis. Death. Hibernation was a generous gift-giver.

“The sickness should be not be so pronounced. How long have we been asleep?” he said. He pinched the bridge of his nose, pressed fingertips against closed eyes until coloured sparks rained. He shook the storm of memories out, concentrating on the moment; on escape, and survival. “We are not all dead. I am not going to die. Not today,” he said.

Action helped him, pushing thoughts of what might have happened to the ship, and the sense of responsibility...

Responsibility? Another flash, a tube. A prick of blood on his thumb...

...to the back of his mind.

He pulled himself from the sucking fluid, pressing down with flat palms. He squatted on the lip of the pod, panting with the effort. Out of the freezing pseudo-amniotics, he felt better. The air was chilly, but not freezing as it had been the last time he woke. Their voyage was over. They were no longer in space, of that he was sure.

He reined in his aggression. He was behaving like an animal, his brain falling back on atavistic patterns. The operations of his neocortex were scrambled, his human mind was racing to piece itself back together. He could not trust himself until it did. He was working on instinct alone.

The Lost and the Damned (The Horus Heresy Siege of Terra Book 2)

The Lost and the Damned (The Horus Heresy Siege of Terra Book 2) Pantheon

Pantheon Man of Iron

Man of Iron Konrad Curze the Night Haunter

Konrad Curze the Night Haunter The Lost and the Damned

The Lost and the Damned Dark Imperium

Dark Imperium Hoppo's Pies

Hoppo's Pies Dark Imperium: Plague War

Dark Imperium: Plague War Dark Imperium: Godblight

Dark Imperium: Godblight Crash

Crash Titandeath

Titandeath Corax- Lord of Shadows

Corax- Lord of Shadows The Nemesis Worm

The Nemesis Worm Wolfsbane

Wolfsbane The Painted Count

The Painted Count The Death of Integrity

The Death of Integrity Perturabo: Hammer of Olympia

Perturabo: Hammer of Olympia Evil Sun Rising

Evil Sun Rising The Emperor's Railroad

The Emperor's Railroad Shadowsword

Shadowsword Pharos

Pharos Stormlord

Stormlord Throneworld

Throneworld The End Times | The Rise of the Horned Rat

The End Times | The Rise of the Horned Rat Death of Integrity

Death of Integrity Omega Point

Omega Point Omega point rak-2

Omega point rak-2 Dante

Dante The Ghoul King

The Ghoul King The Devastation of Baal

The Devastation of Baal Reality 36: A Richards & Klein Novel

Reality 36: A Richards & Klein Novel The Rite of Holos

The Rite of Holos Champion of Mars

Champion of Mars Crusaders of Dorn

Crusaders of Dorn Baneblade

Baneblade