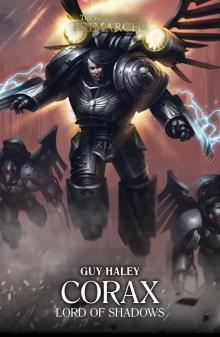

Corax- Lord of Shadows Read online

Backlist

The Primarchs

VULKAN: LORD OF DRAKES

JAGHATAI KHAN: WARHAWK OF CHOGORIS

FERRUS MANUS: GORGON OF MEDUSA

FULGRIM: THE PALATINE PHOENIX

LORGAR: BEARER OF THE WORD

PERTURABO: THE HAMMER OF OLYMPIA

MAGNUS THE RED: MASTER OF PROSPERO

LEMAN RUSS: THE GREAT WOLF

ROBOUTE GUILLIMAN: LORD OF ULTRAMAR

More Raven Guard from Black Library

CORAX

Gav Thorpe

SHATTERED LEGIONS

Edited by Laurie Goulding

DELIVERANCE LOST

Gav Thorpe

SOULBOUND

George Mann (audio drama)

THE GELD

George Mann (audio drama)

Contents

Cover

Backlist

Title Page

The Horus Heresy

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

About the Author

An Extract from ‘Corax’

A Black Library Publication

eBook license

The Horus Heresy

It is a time of legend.

Mighty heroes battle for the right to rule the galaxy. The vast armies of the Emperor of Mankind conquer the stars in a Great Crusade – the myriad alien races are to be smashed by his elite warriors and wiped from the face of history.

The dawn of a new age of supremacy for humanity beckons. Gleaming citadels of marble and gold celebrate the many victories of the Emperor, as system after system is brought back under his control. Triumphs are raised on a million worlds to record the epic deeds of his most powerful champions.

First and foremost amongst these are the primarchs, superhuman beings who have led the Space Marine Legions in campaign after campaign. They are unstoppable and magnificent, the pinnacle of the Emperor’s genetic experimentation, while the Space Marines themselves are the mightiest human warriors the galaxy has ever known, each capable of besting a hundred normal men or more in combat.

Many are the tales told of these legendary beings. From the halls of the Imperial Palace on Terra to the outermost reaches of Ultima Segmentum, their deeds are known to be shaping the very future of the galaxy. But can such souls remain free of doubt and corruption forever? Or will the temptation of greater power prove too much for even the most loyal sons of the Emperor?

The seeds of heresy have already been sown, and the start of the greatest war in the history of mankind is but a few years away...

One

strategos

Roboute Guilliman neared his brother’s hiding place. He didn’t need to see him to know it. His brother’s presence prickled the hair on the nape of his neck, the sensation prey felt before the killing bite. Guilliman was wary. He had won, but he could still fall. In the shattered grand concert hall, shadows were everywhere.

His brother was lord of the shadows. This was his kingdom.

Stepping carefully over a pile of bodies oozing life fluids, he aimed the Arbitrator upwards, towards the top of a shattered column. Often, his brother attacked from above. Darkness and height defined his ambush technique. There was nothing there. He moved on.

‘Your armies are scattered,’ Guilliman boomed. ‘Your worlds are taken. Your last fortress burns. Do you yield, brother?’

The faintest hiss of air was the only warning Guilliman got of the attack. His brother leapt from a shadowed corner of the broken floor above. Black space took on human shape and dived at him. Guilliman pivoted and leant back to dodge a cruelly curved set of claws aimed at his helm.

‘A perfect decapitation strike!’ Guilliman said admiringly. ‘Narrowly evaded.’

His brother went into a roll and sprang up to his feet. Unlike Guilliman, he was unarmoured, clad in charcoal-black from head to toe, his face smeared with the ashes of his empire. A small chest-plate of ceramite was his only physical defence; the rest came down to stealth and guile. It was a strategy that had almost worked.

Almost wins no wars.

Guilliman’s brother attacked again. The claws mounted on the back of his hand fizzled with disruptive energies. Even in full sight he was hard to see. He moved with such staggering speed his motion blurred.

‘Yield! You have lost!’ shouted Guilliman. He had no wish to hurt his brother, but his opponent came on regardless.

Claws whistled around the XIII primarch, jabbing one moment, slashing the next, always in motion, presenting a wall of adamantium. Guilliman left his sword sheathed, dodged the blows and retreated, waiting for the right moment to strike.

It was a small window of opportunity, a fraction of a second where the chest-plate was unprotected by either claw. Without conscious thought Guilliman reacted to the opening, punching forward hard.

The Hand of Dominion flared with the release of power. Guilliman’s brother flew backwards, the chest-plate left broken and smoking by the blow of the power fist. He slammed into the wall, and fell to the rubble covering the ground.

‘You are beaten, brother. Yield.’

The figure sprawled on the floor stared up at him, his black eyes unreadable. His body radiated tension as he gathered himself to spring.

Guilliman planted a boot gently upon his shattered breastplate, forcing the other primarch back down.

‘Do not attempt to rise. You are beaten,’ he said.

The figure relaxed, and sprawled.

‘Do you yield?’ Guilliman repeated.

The figure considered. The sounds of gunfire outside the grand hall were popping away to nothing. Flights of aircraft screaming through the sky no longer unleashed their ordnance. Black eyes strayed to the dead littering the hall.

The war was over.

‘I yield,’ said Corvus Corax.

Guilliman smiled. ‘Good.’ He removed his boot. ‘End simulation!’ Guilliman called. ‘Authority prime.’

A machine answered back.

Voice print acknowledged. Roboute Guilliman, thirteenth primarch, progenitor of Ultramarines Legion. Simulation ending.

The unpleasant electricity of the strategio-simulacra buzzed through the back of Guilliman’s skull. Like an ice sculpture melting under a fusion beam, the battlefield dissolved. Segments of cogitator-spun dreams dripped away, revealing reality behind. There was a moment of disconnect. According to his subjective perceptions, Guilliman was standing and armoured. It took a moment to recognise the recumbent figure lying on the couch next to Corax as himself.

Prepare for reintegration, droned the machine. A necessary warning.

Guilliman’s sense of location underwent a dramatic shift. It took an act of will not to open his eyes and draw a drowning man’s panicked breath. Corax, who had used the strategio-simulacra fewer times, barely managed to maintain his dignity. His limbs flailed about before stilling.

‘Your reaction to the machine is improving. You are becoming accustomed,’ said Guilliman. His voice croaked. His extremities tingled. Being immersed did odd things to the body.

Corax opened his eyes. Their complete blackness gave him a faintly

alien air.

‘I dislike the disconnect, but the cognitive dissonance is lessening,’ said Corax. He sat up on the immersion couch and pulled the magnetic cradle from his head. ‘Though I see no reason to repeat this exercise. I think now you have the measure of me. There is probably nothing more you can learn from my techniques.’

‘You beat me three times,’ said Guilliman. ‘A feat few have managed.’

‘Three from twenty,’ said Corax. ‘You learn very quickly.’ He stretched his arms and grimaced. ‘Those were my best strategies. You countered them all.’

Guilliman stood. His limbs too were stiff. ‘The strategio-simulacra is an amazing machine. I have never experienced anything so convincing. Our ancestors must have struggled not to lose themselves in these devices, but for all its wonders it does weaken the body.’ He held out his hand to his brother. ‘It is a marvellous toy, and will be a useful tool, but it is not entirely healthy. If you wish to call an end to our exercise, I am willing.’

‘I do. Perhaps it is for the best there are no more examples surviving.’ Corax took the offered hand without rancour. Defeat had not embittered him. Guilliman pulled him to his feet.

‘I am sure our father’s scientists or the tech-lords of Mars will unlock the simulacra’s secrets soon enough,’ said Guilliman. ‘A new age of enlightenment is upon us. The secrets of the ancients will be ours again. One day, maybe every Legion will have its like. If one ignores its drawbacks, we can see that it is kinder to the mind than a hypnomat, and allows the consciousness to interact fully with the lessons, preserving a man’s self-determination and therefore allowing faster learning. We must make mistakes in order to learn, after all.’

Corax glanced around at the machine and the silent men tending to its needs. It was something from the lost Ages of Technology, retrieved by Guilliman on one of his campaigns. In its original format it would probably have been smaller, but the Imperial technologies that had restored it to full function rendered it enormous. Its mechanisms encompassed the room they were in within thick, complicated walls; everything, all the operating stations, connection points, medical devices and the two dozen immersion couches at its centre, were inside the device. Whistling coils and banks of clattering cogitators extended to fill most of the ship’s hold where it was kept.

‘I would be careful with it. It is good some of the old knowledge was lost. I am sure this false reality holds its own evils.’

‘Perhaps,’ Guilliman allowed. ‘But we are wiser now than before Old Night, and when the Imperium is complete, nothing shall be impossible. Now, perhaps you will join me for further discussion this evening? I have matters to attend to that cannot wait.’

‘I have several things to see to myself. Fresh orders from Terra. I must begin preparations to leave.’

‘We will be parting ways soon,’ said Guilliman regretfully.

Corax nodded. He had a grim little smile. It looked pained. He laughed sincerely enough, but smiling seemed to come hard to him. A side effect of a childhood behind bars, Guilliman thought.

‘This evening then, my brother,’ said Corax. ‘I look forward to it.’

Two

the fall of the house of adrin

There were so many parties. Aranan Armadon Adrin would not have minded that, but they were so rarely just parties. The lengthy run of Salvation was approaching. Over the next three months, between their grinding work shifts, the Kiavahrans would be forced to celebrate Uprising Eve, Atomic Day, Saviour’s Day, Compliance Night and the Renewal of the Oath. A lot of business was conducted at receptions in between. Aranan had far too many such events to attend.

The last party he was ever to attend was held at the Museo Kiavahr, a prestigious setting for any event, and a subtle thumbing of the nose at the planet’s new Mechanicum masters. Kiavahran politics were all so petty, Aranan thought. He lurked at the edge of things, deliberately avoiding eye contact and watching the tech-guilders attempt to make small talk with their half-human masters. Two things kept them from success. Firstly, the Mechanicum’s tech-priests were not given to small talk. Secondly, every guilder face in the room burned with resentment behind their forced smiles.

Still the attendees persisted with speaking to each other, neither side understanding the other, but united briefly in the slow, ritual torture of official socialising. The Kiavahrans were unctuous and insincere. The Mechanicum priests, bizarre cyborgs whose cowls hid minds of diodes and wire, could not help but be calculating. It was not a happy mix. The function paraded Kiavahr’s dysfunction for all to see.

‘What a disaster,’ Aranan said to himself. He swirled his wine around in his glass and watched the tiny vortex. The drink was weak, and insipidly warm. A familiar voice nearby had him lift his head.

There was Ev Tenn, not four metres away, one of the few men close to his own age at the function. Ev Tenn had been a wild thing, a legend on the social circuit when Aranan was taking his first, faltering steps out from behind his mother’s protection. In truth, Ev had been one of his cousin’s friends, not his. They had never been close, but Aranan made for him with relief shining from every pore.

‘Ev!’ he called. ‘Ev!’

There was no recognition. Ev didn’t look in his direction. ‘Ev!’ he called again, waving like a fool. He attempted to shove his way past a Mechanicum acolyte the shape of an oven draped in a red robe. Foolishly he expected giving flesh, and banged his elbow painfully on the metal beneath the cloth.

‘It’s me! Aranan Armadon Adrin, Jenpen’s cousin.’

Ev turned from his conversational partner, their dialogue broken by the silent, mutual accord of socialites uninterested in one another. Darting eyes judged, each man silently trying to convince the other that it was he who was the boring one.

‘Ah! Yes, I remember. Little Three-A, all grown up,’ said Ev as he turned to face Aranan. Aranan hated the nickname. It was a number, reducing him to the status of a thing. Ev had always been cruel. He should have turned away, but there was no one else he shared a connection with. ‘How are you? Didn’t you inherit your father’s office last summer?’

‘Don’t remind me about it,’ said Aranan.

‘Well, how are things, eh, Three-A? They don’t sound so good.’

Ev placed a comforting hand on his arm. Aranan was too much a Kiavahran to take the gesture at face value – there was intrigue in every twitch of a guilder’s body – but he was pathetically grateful all the same.

‘Awful,’ he said. ‘Just awful.’ He meant it.

‘I see,’ said Ev. He made a sympathetic face. ‘Bored, eh? You’ll get used to it.’

‘Will I? Look at all this. Surely,’ he said, ‘the Mechanicum can see hosting the annual contract exchange in a museum dedicated to the tech-guilds is nothing but a protest at their presence?’

Ev Tenn kept the smile Aranan remembered, though the eyes that glinted above it had bled out their lust for life, and been refilled with a bureaucrat’s coldness. ‘My dear fellow, the Mechanicum let the tech-guilds hold the reception here. They could stop us. They don’t. They are letting us know they see the insult and they don’t care. They are telling us that whatever we do is pointless. They have all the power now.’ Aranan had little power himself. Already Ev was looking about the room for a route of escape.

‘They still don’t have all our secrets,’ said Aranan, hating the wheedling tone in his voice.

‘That’s the only thing that’s keeping any of us alive,’ said Ev from the side of his mouth.

Aranan looked sour. ‘It’s ridiculous. The Emperor speaks of enlightenment and the end to superstition, and He sets this coterie of priests over us. We might not have the wisdom of the ancients, but we’re scientists, not witch doctors like they are.’

‘Careful, Aranan, that’s treasonous.’ Ev Tenn smiled at a pretty woman alight with pulsing subdermal implants, and swept a glass from her tray. A lit

tle of the old Ev was present in that smile, encouraging Aranan. But the light vanished from Ev’s face as soon as the woman turned away, and Aranan’s heart fell.

‘You’ve changed, Ev.’

Ev’s expression indicated something that was not quite agreement, but nor was it disagreement. Aranan was overplaying his hand.

‘You’ll change too, Aranan. Politics will crush the life right out of you.’ Ev Tenn gripped Aranan’s shoulder firmly and dropped his voice. Sincerity made a brief appearance behind his shell of confidence. ‘Be thankful you had a good run outside all this. You’ve your guild’s honour to think of now rather than your own pleasure.’

Aranan scowled.

‘Chin up now, Three-A. It’s been great to see you. I must be going.’ He uncurled a finger from his glass and pointed across the room. ‘I see that the Hasslian Representative is alone. I intend to get him drunk and harass him into signing a favourable trade deal with my house. If you’ll excuse me, I don’t get a crack at off-worlders often. I have to seize the opportunity when I can. You should too.’

Ev left with a small wave, weaving his way through the red-robed cyborgs and glittering guild masters like a man born to brokering.

Aranan sulked. It wasn’t long until he was wishing he’d taken Ev’s advice and attempted to perform his role, for his introspection was shattered by Deven Terr. The Terr Kir tech-guild had been trying to buy into his father’s interest in whispercutter manufacture for years. With his father dead, it was Aranan’s duty to put Terr off. He had never liked the man.

Aranan lacked the guile to extricate himself from Terr’s company, though to his credit he was too stubborn to be browbeaten. As the conversation droned on and on he kept one eye on the hostesses serving his drinks and the other on the museum chronograph. For Deven Terr he spared hardly a glance.

He resented the chronograph like he resented Terr. It had a face as big as the moon of Lycaeus, covered over in fussy calligraphy and painting which the stylists called ‘naive’, but which to Aranan looked like the work of a child. It was thousands of years old, so they said. He didn’t care a jot. It glowered down at him, ticking off the seconds of his life, chiding him for spending them so poorly. Of course, the clock showed old Kiavahran time. Seeing as the old measure had been supplanted by Imperial reckoning, its display was another snub to the Mechanicum. As far as Aranan was concerned, its judgemental air outweighed its worth as a symbol of defiance. Had it been his decision, he would have smashed it with a hammer.

The Lost and the Damned (The Horus Heresy Siege of Terra Book 2)

The Lost and the Damned (The Horus Heresy Siege of Terra Book 2) Pantheon

Pantheon Man of Iron

Man of Iron Konrad Curze the Night Haunter

Konrad Curze the Night Haunter The Lost and the Damned

The Lost and the Damned Dark Imperium

Dark Imperium Hoppo's Pies

Hoppo's Pies Dark Imperium: Plague War

Dark Imperium: Plague War Dark Imperium: Godblight

Dark Imperium: Godblight Crash

Crash Titandeath

Titandeath Corax- Lord of Shadows

Corax- Lord of Shadows The Nemesis Worm

The Nemesis Worm Wolfsbane

Wolfsbane The Painted Count

The Painted Count The Death of Integrity

The Death of Integrity Perturabo: Hammer of Olympia

Perturabo: Hammer of Olympia Evil Sun Rising

Evil Sun Rising The Emperor's Railroad

The Emperor's Railroad Shadowsword

Shadowsword Pharos

Pharos Stormlord

Stormlord Throneworld

Throneworld The End Times | The Rise of the Horned Rat

The End Times | The Rise of the Horned Rat Death of Integrity

Death of Integrity Omega Point

Omega Point Omega point rak-2

Omega point rak-2 Dante

Dante The Ghoul King

The Ghoul King The Devastation of Baal

The Devastation of Baal Reality 36: A Richards & Klein Novel

Reality 36: A Richards & Klein Novel The Rite of Holos

The Rite of Holos Champion of Mars

Champion of Mars Crusaders of Dorn

Crusaders of Dorn Baneblade

Baneblade