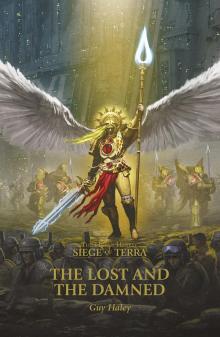

The Lost and the Damned (The Horus Heresy Siege of Terra Book 2)

The Lost and the Damned (The Horus Heresy Siege of Terra Book 2) Pantheon

Pantheon Man of Iron

Man of Iron Konrad Curze the Night Haunter

Konrad Curze the Night Haunter The Lost and the Damned

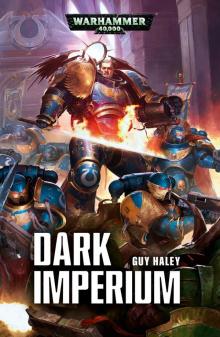

The Lost and the Damned Dark Imperium

Dark Imperium Hoppo's Pies

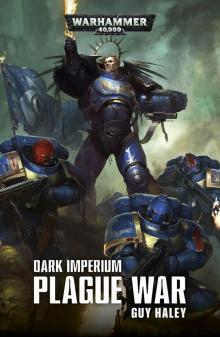

Hoppo's Pies Dark Imperium: Plague War

Dark Imperium: Plague War Dark Imperium: Godblight

Dark Imperium: Godblight Crash

Crash Titandeath

Titandeath Corax- Lord of Shadows

Corax- Lord of Shadows The Nemesis Worm

The Nemesis Worm Wolfsbane

Wolfsbane The Painted Count

The Painted Count The Death of Integrity

The Death of Integrity Perturabo: Hammer of Olympia

Perturabo: Hammer of Olympia Evil Sun Rising

Evil Sun Rising The Emperor's Railroad

The Emperor's Railroad Shadowsword

Shadowsword Pharos

Pharos Stormlord

Stormlord Throneworld

Throneworld The End Times | The Rise of the Horned Rat

The End Times | The Rise of the Horned Rat Death of Integrity

Death of Integrity Omega Point

Omega Point Omega point rak-2

Omega point rak-2 Dante

Dante The Ghoul King

The Ghoul King The Devastation of Baal

The Devastation of Baal Reality 36: A Richards & Klein Novel

Reality 36: A Richards & Klein Novel The Rite of Holos

The Rite of Holos Champion of Mars

Champion of Mars Crusaders of Dorn

Crusaders of Dorn Baneblade

Baneblade