The Ghoul King Read online

Page 3

When we ripped up the floorboards I could only think of the poor bastard that rented us the place. I made Fillip stack them up; I figure why make life harder for people. He grumbled about that all the way to Old Columbus. Right until he died.

I couldn’t get my mind off that box. The damn thing fascinated me. Rachel only left it behind when we were in the city. The rest of the time it went everywhere with her. She took it to bed with her. She spoke to it at night. Thing is, I could have sworn whatever was in there was answering back. I didn’t get a look at it for a long while. Every time I even so much as glanced in that direction, Fillip would shake his head in that way a man does before he cuts your throat.

“Go go, get out of the tunnel, you bandy-legged leech!” Fillip said, slapping at my ass all the way. We’d dug down only as far as we needed to get out under the arena on the other side of the street, and that wasn’t as far down as the original floor of the tunnel, so the ground was uneven underfoot and the ceiling low. My knees popped at being hurried along at such an undignified rate, Fillip smacking at me like I was a donkey. His precious wire rolled out off a spool behind him as he ran. He’d drawn it all himself, he said. Waste of time. I asked him why he didn’t just use a trail of powder to set off the dynamite. He told me to fuck off.

He shoved the roll at me. Rough cardboard made of badly pulped wood, and full of splinters. He probably made that himself too.

“Hold that, you old fool,” he said. He often called me old. I’m twenty-nine, he can’t have been under twenty-five. I’ve aged badly because of the poisons from the war, and I look older. He took out a device from his pocket. A metal box, with an unshielded needle with no gauge and simple switch on the front. He toggled the switch on it to test it. The needle jerked. If it weren’t for that box on the table in the house, that one jolt of out-of-place electricity would have had the angels down on us like furies. He grinned like a devil at the thrill of using his illicit knowledge. For me, it was different. These hands were made to heal. I didn’t want any part of explosions and fighting and lawbreaking, other than the use of the old knowledge. Only for good. I did what I did for mercy’s sake. How can the angels disapprove of that if they truly do serve God?

“Get up into the room, shitass!” snarled Fillip. “Or do you want to stay down here and get a throat full of rock shards?” Once again he laid his hands on my buttocks and pushed.

“Stop that!”

“Shut up, you old woman,” he said, shoving me into the room. He snatched the spool of wire from me, and critically peered down the length to see if there were any breaks, then tugged it gently. He grunted in satisfaction. He grunted a lot, pig of a man. “Right.” He pulled out his pliers from his belt, and set about wrapping the wire around a pair of contacts built into the back. Contacts. I learned a lot. I know I said that I was only interested in healing, but Rachel’s Seekers talked about all manner of forbidden knowledge freely with each other. I tried not to hear at first, but I couldn’t! I was with them too long.

He made me check the time on my watch every thirty seconds, so it felt, waiting for the appointed time of half past three in the morning. When it finally came, he leapt up with glee. He flicked his switch. The needle did not move. He frowned and flicked it back and forth furiously. I tried not to look pleased to see him thwarted, although truly I was. Had it finished there and then, I would have taken my leave and gone on my way. I wish I had. I was about to stand and dust off my trousers, bid him good riddance and go, I swear to God.

There came a cough from under the street. The ground shifted. The fittings of the house, such as we’d left in place, rattled. A blast of filth and dust bellied out of our tunnel, coating everything in grit.

Fillip whooped.

“It worked!” he said, clapping me on the arm in sudden and unlooked-for comradeship. “It worked! Hot damn!”

I spluttered. It was like breathing razors in there.

“Come on, come on, you old whiner, we have to get out of here!” He rushed about, full of nervous energy, snatching up such tools as he had not already put into his pack. All my gear was prepared. My pack, dreadfully heavy, leaned against the door. I went for it.

There on the table before me was Rachel’s little box, the warm brown wood and brass fittings coated with dust.

Something in there called to me. It . . . it got into my head. I forgot my pack and let it slip back to the floor. My hands reached for it not of their own volition. Something in there had a hold of my mind, I am sure, as you your holiness have a hold of it now. If I had known what it was right from the start, I would never have listened to Rachel’s offer.

Fillip appeared between me and it, face hard. “You leave that be! Get your pack, old man!”

Truth be told, for once I was glad of his rudeness. The spell was broken. I took up my pack, and we hurried out of the back door of the house.

It was night, and cold. Looks cold out there now, in the street. Winter’s early this year. Frost crunched under my feet on what sparse grass found purchase around the houses and the air was sharp in my lungs. The combination of the dust and the cold had me hacking hard. Fillip had no care for my discomfort, and ran on ahead, assuming I would follow. Of course I did. To the north the sky was stained with fire that framed the houses, licking up the side of the Pit. A hue and cry went up from the streets. Towers of orange sparks whirled skyward, born on the steeds of their own heat, until they flickered and died and fell. A drift of ashes sifted from the sky. I stopped to watch. The clamor of bells and shouts became entrancing, music for the dancing motes.

Fillip hurried back to me. “The fuck!” he hissed into my ear. “Get on with you!” he said, his fingers digging into my arm. He dragged me down the lane behind the houses. Behind us, the arena cracked and splintered.

It was a tunnel under the east wall, in that spot where there’s a blind stretch between the Duball and Lockburn towers. That was how we got out. Thomas had dug it on his own inside a woodshed. We were to meet him, Bernadini, and Rachel there. Fillip knew exactly where it was while I had no clue. They didn’t trust me enough to tell. They were a tight crew, and I had been with them less time than the rest.

“Where the hell are they?” I said as Fillip bundled me into the shed.

“Quiet!” he hissed. “The Duball tower is thirty yards from us. Shut up!”

We waited tensely in the dark. Twenty minutes after they were supposed to be there, Rachel, Bernadini, Thomas, and a fourth man came into the woodshed in a flurry of small noises, bringing in the smell of cold night air and fresh smoke.

“You got him!” said Fillip.

“Shhh!” warned Rachel. “Jaxon, Bernadini’s hurt. See to him.”

There was precious little room in the shed. Thomas had disposed with the lumber, but he’d replaced it with a pile of unevenly heaped earth hidden under tent cloth. We were all banging into each other, noisy as drunks coming home and trying to be quiet. Bernadini was a big man, and he thrust his arm out at me. It hit me in the chest about as gently as a falling tree, pushing me back. His cheeks glistened with tears, his eyes sliding about in silent pain. He was swaying. Blood dripped on the floor. Outside, dogs bayed.

“We need to get across the river,” said Rachel.

“A minute, a minute!” I said. I had no time to clean Bernadini’s wound. I wrapped his arm as best I could with a bandage. Bernadini gasped and clicked his teeth with every wind of the cloth.

Shouting followed the dogs.

“The dogs have your scent,” said the knight calmly. “They’ll be here directly.” That was the first time I heard him speak. He had a quiet voice, unconcerned, like he was making an observation on the plot of a play, detached from what was going on around him.

“Into the tunnel,” said Rachel.

Fillip yanked back a tarpaulin on the floor, revealing the tunnel mouth covered over with loose planks. He and Thomas set about moving them, quietly as they could. The shouting was getting nearer. Fillip waved us down and t

hrough. When I looked back, he was pulling more dynamite from a belt under his shirt, lots of dynamite. The damn fool had it hidden under his shirt all the time. Bernadini staggered along next to me. I prayed he wasn’t going to want me to support him. He was twice my weight.

I went into the tunnel. I found out what Thomas had done with the lumber. He’d used it all as props, very closely spaced. And they needed to be too. We were going right out under the wall and the tunnel was shallow. Rachel went first, then Thomas and the knight, still chained. Bernadini and me. I looked back. Fillip was still in the lumber shed. Bobbing lamplight lit up the pale wood of the lumber bracing. The charred tips of the palisade timbers driven into the ground poked through the roof of the tunnel, four of them, spaced a foot apart like giant, black teeth waiting to descend.

We passed the wall and were technically out of the city, but we were still trapped. Rachel said something, and all the lamps were doused. We ran another ten yards into a square of indigo night, tumbling out of the tunnel, down the bank, toward the river. Robyn waited in a stand of trees, our sixth conspirator, seven horses picketed behind her. Rachel, Quinn, and Thomas ran toward her. It was very dark and quiet outside the walls; all the commotion was on the far side of the palisade. Things were going our way, until Fillip yelled “Clear!” Unnecessarily I thought; he was the last out of the tunnel. That was the last thing that went through my head before I was sent sailing through the air.

A yellow cloud of fire and racing, red-hot splinters of wood roared out into the night. Fillip went head over heels. Bernadini landed on his wounded arm with a piteous cry. Clods of earth pattered down all around us, getting in our eyes and mouths. My ears rang. Quinn, Rachel, Thomas, and Robyn were struggling with the horses who were rearing like crazy at the noise, kicking at anyone who came near them.

With a yawning screech, the timbers of the wall toppled outward, ringing off each other with musical, xylophone notes as they bounced on the ground, those that fell dragging on the ropes that bound them all together and pulling more down, opening up a breach six yards across and weakening the palisade for double that distance either side. Smoke hazed the gap. The shed we’d exited out of was burning madly, walling the gap with fire. On the far side someone was screaming without drawing breath, a man, but high-pitched, like a dying animal.

“I never meant to . . .” said Fillip, openmouthed.

Quinn and the others rode to our side. The horses were still tossing their heads and whinnying. Rachel slid off her horse and helped me boost Bernadini onto his.

“That wasn’t very smart,” said Quinn. “You must have used four times too much explosive.”

“Dynamite. It was dynamite,” said Fillip. “I’ve never used it before tonight. I’ll know better next time.”

“Fine time to be experimenting,” said the knight. “You’ll be lucky to see a next time. Some rescue.”

Lights were coming on along the wall. Voices. A musket cracked. The bullet sang through the air some ten yards away. It wasn’t done yet. Torches were gathering in the gap. We would soon be seen.

“You can go back!” snapped Rachel. She calmed her mare and swung back up onto it. Fillip came to her and handed her the box. She glared at him. He backed off, apologizing.

“I could have got out on my own,” said Quinn.

“You’re out now.”

“Now what?” said Quinn.

“That way,” she said, pointing to the ferry station down on the Scioto River. “The ferryman’s a friend.”

“You go round blowing holes in cities like that, you’re going to run out of friends real quick,” said Quinn, and spurred his horse on. What else could the rest of us do but follow?

* * *

This is how Rachel got to me. I was working as a cook’s assistant and plant-fetch for the apothecary at the Monastery of Sainted Electrics between Chillicothe and Portsmouth on the Virginia road. They’re sanctioned engineers, hiring themselves out for hundreds of miles around. Your town got a license, they’re the sort that will put in the power systems. I was there as a punishment, but it suited me. Healing is all I ever wanted to do. I’d been censured for chasing the Old Knowledge, and I think I’d been put there to test me; to see if I’d steal. But the knowledge the brothers had, all pistons, wires, and cogs never interested me. I had been in court, made my peace with God, and sworn never to dabble again. Never, I swear. God in his justice had decreed that I serve the holy brothers. I found them not so holy, and less than welcoming. In my humility and shame I took it upon myself to do the best I could. I could help those in need as the Lord decreed, and my heart urged me to comply.

I met Rachel at the Chillicothe market, when I was picking over cabbages. I can’t remember why we needed cabbages. The brothers had their own land. They grew their own cabbages. But I had been sent out specifically for cabbages that time, there’s not a doubt of that, and that’s where she came and stood beside me.

“The crop’s good this year,” she said. Her looks arrested me. I am not a lustful man, but our thoughts can betray us all, and Rachel was beautiful in her way. Outlandish dress, though, unwomanly. Always in trousers and leather work garments even when she was trying not to be noticed. I think she liked it. I think she wanted people to notice her and to wonder who she was, this woman. It is too much for the male mind to accommodate, such brazen display of the thighs and buttocks. She wore her jacket high cut, for ease of movement, she said. I never liked walking behind her, my eyes were pulled to her behind. It was sinful! She was a temptress in every way, and she dismayed me. It made me sad. I am aged before my time and the effects of the war have wrinkled me. She would never want one like me.

“They are fair cabbages, yes,” I said. I wished she would leave me alone.

“You are Jaxon, aren’t you?” she said, all conversational. “I have heard about you.”

“People talk too much,” I said. I chose three cabbages at random. The brothers would scold me if they were not the very best, but I was alarmed. I wanted to get away from her.

“I also heard that you are a talented healer.”

I could have said right there, no ma’am, I am not Jaxon, I am not a healer. But I didn’t. I sealed my fate that moment when I decided to reply at all. I think about it a lot.

“Yes, ma’am. Jaxon, the cook and doctor’s assistant at the monastery.”

“You live at the monastery, but you are not a brother.”

“No, ma’am.” I looked at my hands. They were stained with sin as much by dirt. “They wouldn’t let me take orders.”

“Good,” she said, and patted my arm, and left. I didn’t find the document she’d slipped into my pocket until I was back at the monastery, chopping the cabbages for stew.

She’d slipped it in without me so much as noticing. A treatise on the transmission of disease through dirty water. Very ancient, from the Gone Before. The pages were printed new, on poor paper, but the knowledge was old, very old. I know that. I know I shouldn’t but I do know it. I don’t have the paper anymore, before you ask. It’s gone with everything else I had. But that’s alright, because I read it, and it’s up here, see? In my mind. You can’t keep us from the knowledge forever. You can’t.

On the back there was a note to me. A series of numbers. Map coordinates and a date, I figured out eventually. I wasn’t going to go just like I wasn’t going to agree that I was Jaxon the healer, but I did. I waited in the freezing dark terrified I’d die. She came, and Bernadini. Told me what she was about, then gave me a choice. Come with her, learn the things she knew I yearned to know. It wasn’t much choice, the other option was that she’d have to kill me.

She was convincing, and I don’t mean just about the threat. She seemed to know a lot about me. She knew I still wanted to know how to help people, people who die from things our ancestors could heal with the click of their fingers. She knew what I’d written even, in my journal, the words that got me punished.

“You wrote, ‘There is little in the world t

hat is God’s will, but a lot that is the angels’.’” She smiled when she quoted it at me.

She knew that I was a coward. She worked on that. She flattered and cajoled and Bernadini smiled at me while he held a massive knife upon his knees. Like I said, I didn’t have any choice, not really.

This Quinn, he had even less of an opportunity to say no. We blew up his prison and dragged him out. What could he do? We crossed the river. For five dollars, the ferryman had made himself absent. When we were on the other side, we cut the rope and sent the ferry barge off downstream. Then we hightailed it to our stash, leaving the flames of the city and the shouts and the dogs far behind.

Rachel had had our gear hidden in a broken-down barn right out on the edge of the zone, that decontaminated area around Newtown five miles across for crops, livestock, and settlement. You angels did it. Back then I thought you had our best interests at heart. Where it ended, the wild woods and scrub began. That’s the beginning of the frontier, so close to Newtown. Go out west that way and you’re into the haunted lands, past the ruins of Cincin and Indianapolis. Even before the Emperor’s War there was nothing but animals and red men out that way, past that are the Great Plains and the herds there. If it weren’t for this being the last place on earth where civilized men can live, then the angels would never have built Newtown. They’d have let the place stew in its own poisons as a warning. I don’t presume. Rachel said so, and I believed her. I gave up presuming a while ago.

We went into the barn without dismounting. Rachel leapt off her horse and pushed the doors to. Robyn bounded up into the hayloft, dislodging showers of rat shit as she went, and took up position by the winch door in the gable.

“Nobody’s coming!” she hissed. “Torches out by the city palisade, not coming out into the country.”

“What makes you think they’d let you know they are coming?” said Quinn.

“He’s right,” said Rachel. “Get the equipment. We have to keep moving.”

The Lost and the Damned (The Horus Heresy Siege of Terra Book 2)

The Lost and the Damned (The Horus Heresy Siege of Terra Book 2) Pantheon

Pantheon Man of Iron

Man of Iron Konrad Curze the Night Haunter

Konrad Curze the Night Haunter The Lost and the Damned

The Lost and the Damned Dark Imperium

Dark Imperium Hoppo's Pies

Hoppo's Pies Dark Imperium: Plague War

Dark Imperium: Plague War Dark Imperium: Godblight

Dark Imperium: Godblight Crash

Crash Titandeath

Titandeath Corax- Lord of Shadows

Corax- Lord of Shadows The Nemesis Worm

The Nemesis Worm Wolfsbane

Wolfsbane The Painted Count

The Painted Count The Death of Integrity

The Death of Integrity Perturabo: Hammer of Olympia

Perturabo: Hammer of Olympia Evil Sun Rising

Evil Sun Rising The Emperor's Railroad

The Emperor's Railroad Shadowsword

Shadowsword Pharos

Pharos Stormlord

Stormlord Throneworld

Throneworld The End Times | The Rise of the Horned Rat

The End Times | The Rise of the Horned Rat Death of Integrity

Death of Integrity Omega Point

Omega Point Omega point rak-2

Omega point rak-2 Dante

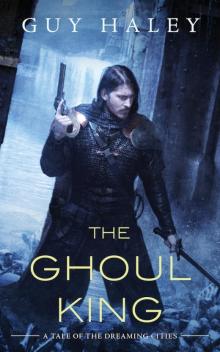

Dante The Ghoul King

The Ghoul King The Devastation of Baal

The Devastation of Baal Reality 36: A Richards & Klein Novel

Reality 36: A Richards & Klein Novel The Rite of Holos

The Rite of Holos Champion of Mars

Champion of Mars Crusaders of Dorn

Crusaders of Dorn Baneblade

Baneblade